- [Open Access] Fobbe, Seán. “Sind zwanzig Jahre zuviel? Die Dauer von Verfahren vor dem Bundesverfassungsgericht” (RECHTS|EMPIRIE 2022)

- [Open Access] Source Code (Zenodo)

Background Link to heading

In December I published an analysis of the length of proceedings before the German Federal Constitutional Court (BVerfG) in RECHTS|EMPIRIE, a German science blog. The links in the info box above will direct you to the original text of the article and the source code (in R). Below is an English summary.

English Summary Link to heading

Introduction Link to heading

The German Federal Constitutional Court (BVerfG) is not only a guardian of justice, but also a guardian of time. Judgments in court proceedings should be just, but they should also be prompt. This maxim has been pithily summarized as “justice delayed is justice denied” (Gladstone) or “swift justice is the sweetest” (Bacon). In German it is known as the “Beschleunigungsgrundsatz” and enshrined in domestic statutes, the constitution and the European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR).

The Role of the Beschwerdekammer Link to heading

I briefly discuss the role and jurisprudence of the Beschwerdekammer, the special panel of the BVerfG that reviews the length of constitutional proceedings. Since its creation in 2011 it has ruled on few cases and published only seven decisions. Based on the case law of this special panel it would appear that, regarding its own constitutional proceedings, the BVerfG generally considers a length of five to seven years to be acceptable.

The role and composition of the Beschwerdekammer represents a prima facie violation of the principle nemo judex in sua causa (no one can be a judge in their own cause), as the judges rule on the quality of their own professional conduct and that of colleagues in a very small court. There exist only limited safeguards, such as the exclusion of the rapporteur of an impugned decision from Beschwerdekammer proceedings.

However, there do not appear to be any alternative options that would not undercut the special role of the BVerfG in the German constitutional framework. The endless saga surrounding the new disciplinary panel of the Polish Constitutional Court demonstrates the danger of external interference with an apex court.

A Silver Lining Link to heading

There is a silver lining to this situation: if BVerfG judges are judges in their own professional causes, then an empirical analysis of its activities will allow us to augment our understanding not only of the practice of the court, but also of its normative stance on the acceptable length of constitutional proceedings.

The official statistics of the BVerfG are quite terse with regard to the actual length of proceedings. Specifics are only available for constitutional complaints and do not cover durations of more than three years.

To gain a better understanding of the court’s practice I turn to the Corpus der Entscheidungen des Bundesverfassungsgerichts (CE-BVerfG) (Fobbe 2022), which documents all published BVerfG decisions since 1998, plus metadata. This metadata includes the year in which proceedings were initiated and the date the judgment was rendered. From these I calculate an estimate of the length of proceedings in years. Several notable limitations are discussed and sensitivity analyses performed (see source code for full details).

Results Link to heading

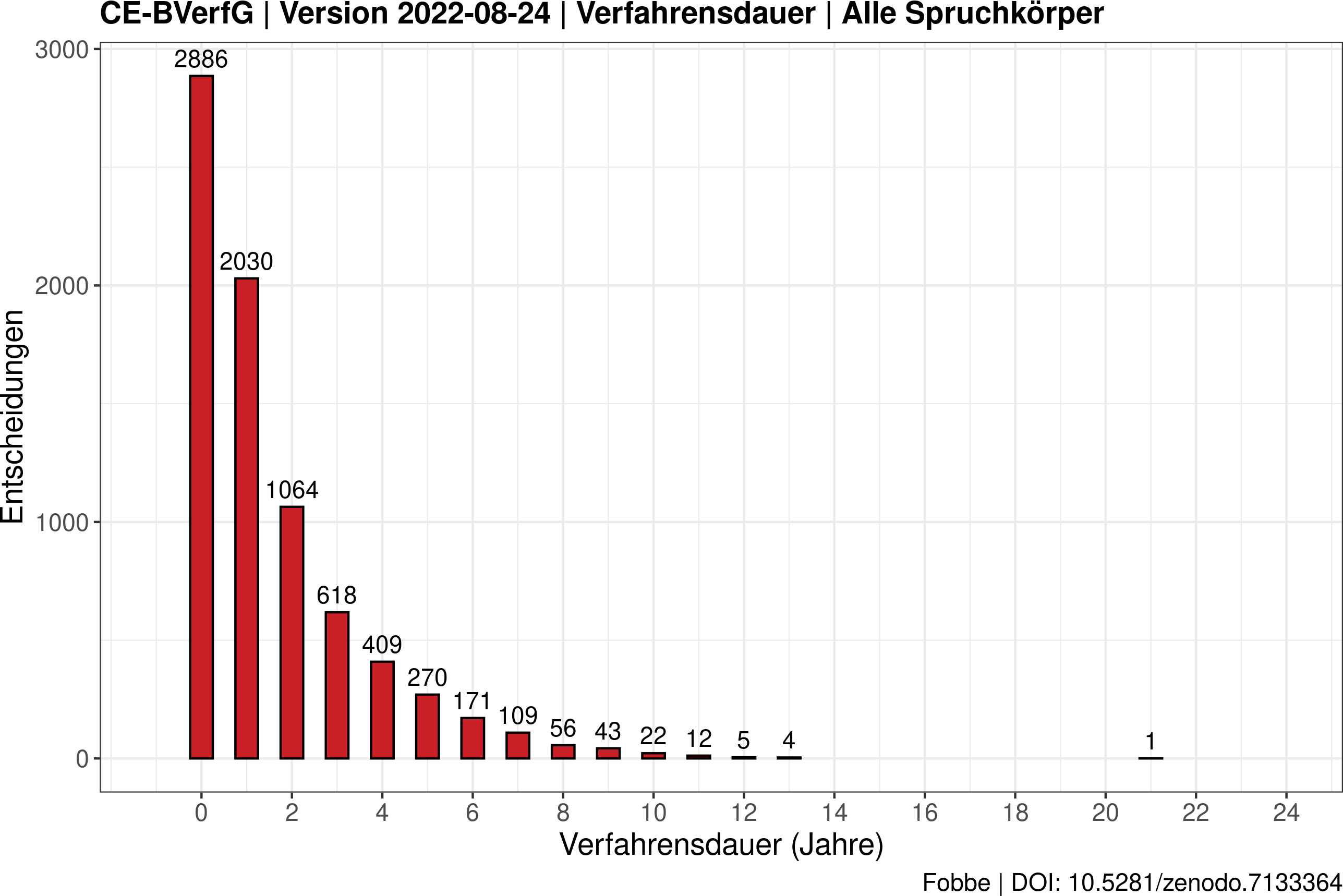

The data consists of 8,407 published decisisons. After excluding procedural decisions (e.g. costs), 7,700 decisions remain. I visualize the frequency distribution of length in years via bar plots for all decisions, senate decisions (important cases) and panel decisions (all other cases). It is immediately obvious that many decisions take more than three years.

44 decisions even hint at proceedings of 10 or more years. A single outlier decision was handed down after slightly less than 21 years.

The median for senate proceedings is 2 years and 1 year for panels, with a worst case measurement error of 4 months. The mean for senate proceedings is 2.87 years and 1.35 years for panel proceedings, with negligible measurement error.

After a close reading of the full text, the single 21-year-decision appears to be a curiosity of legal history, not a scandal. The petitioner challenged an abuse fee (Missbrauchsgebühr) levied by the BVerfG. However, such decisions are final and there exist no formal remedies to challenge them. The application was clearly without merit. This incredible delay in an absurd situation is reminiscent of a famous play linked to the Theatre of the Absurd: Waiting for Godot.

Bar Plot Link to heading

The x-axis shows length of proceedings in years, the y-axis the number of decisions. This diagram includes all decisions from both senates (8 judges) and panels (3 judges).

Experimental Visuals Link to heading

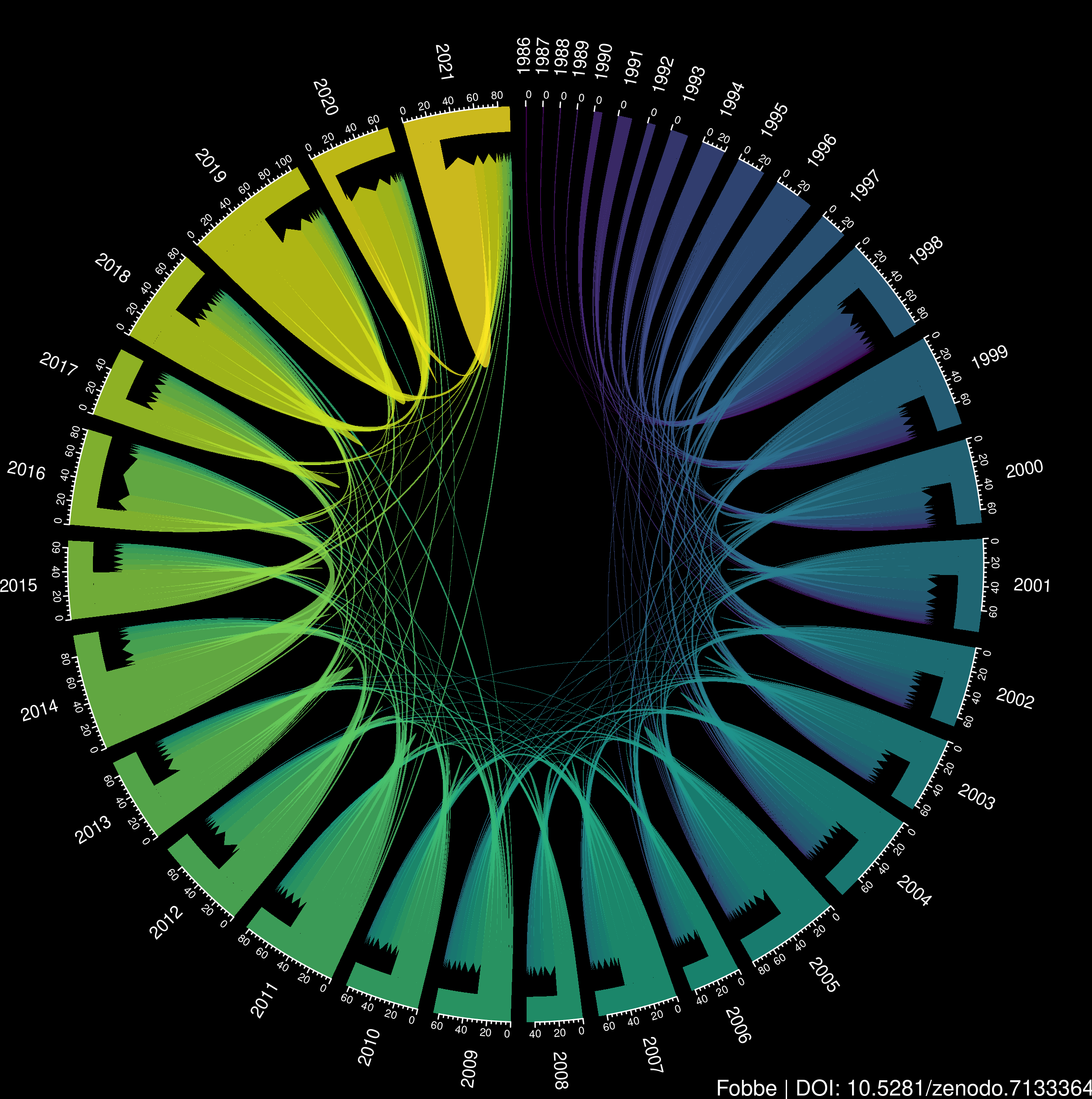

The article closes with experimental visualizations: Chord diagrams. These have known limitations (the human eye being unable to judge angles accurately, difficult to interpret without assistance), but can represent the data in the original in-year/out-year format and are able to show the change over time in length of proceedings. The diagrams are interpreted as an example for future users.

Length of Proceedings (Senates) Link to heading

Length of Proceedings (Panels) Link to heading